I will be completely transparent and start by saying that this blogpost itself has been rewritten a couple of times since its original idea. Given the topic we are going to discuss, it seems fitting that that happened.

In the beginning of 2019, we took over a Rails project. On the surface, it looked like a typical Rails app with an integration to a payment service. The fun began when we started to take a closer look at the codebase.

Mocking an API

Let’s say we want to mock a request that makes a payment. Normally, we’d use something like webmock or VCR in order to fake that interaction with the real API and have an expected result that we can use in our tests. Something that would allow the code to run exactly as it would run in the production environment, with the only difference being the return value we get from the request. We don’t need to write code in the controller to check what environment we are on. The code is the same, the output of the HTTP call is what’s different. If you want to know how to do this, the folks from Thoughtbot have a great post about that.

Unfortunately, the codebase at that time didn’t have any automated tests and the development team opted for another approach to testing. Any time they had any major updates, they would have someone from their team run through a list of tests and manually assert that everything is working as it should or report any regressions they would find.

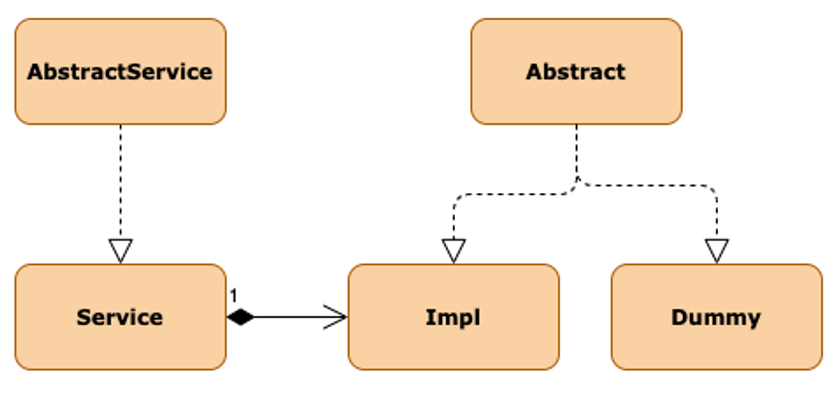

So, how did they mock the external API? In short, for every endpoint of the external API, they added a Dummy and an Impl class. You can probably guess from the naming, but to be perfectly clear, the Dummy class version is the mock and the Impl is the actual implementation of the endpoint. Ok, now we have two classes for the same endpoint. One that handles the mock for the development environment and another that handles production.

It’s a bit of unnecessary indirection but at least we have a complete separation of the implementations. Except, not really. Something I haven’t mentioned yet is that both Dummy and Impl classes were inheriting from a common Abstract class. The Abstract classes mostly served to ensure that both versions had the same methods implemented, but, in some cases, actual logic was in the Abstract class. This coupled with the fact that for each endpoint we would have a Service class, that served as the main entrypoint to that service, that itself would inherit from an AbstractService, just to return the Impl class, added up to be a lot of indirection.

All this is difficult enough to actually follow when looking at the code, let alone just reading some vague description. Here’s a diagram to help visualize it.

This is a simplified version of the actual structure. The diagram doesn’t show the models used in each class and we had this for each request in the API. Sometimes, trying to find where a particular method was defined, was like trying to find a needle in an haystack.

This strategy worked at the time it was needed and there was nothing particulary wrong with it. It served its purpose but trying to maintain it was proving to be challenging. Especially now that we no longer need the Dummy classes. We had inheritance between two classes when it would be fine to merge everything into a single class. We’ve since refactored this and removed a lot of that indirection.

Chances are you are familiar with the Donald Knuth quote: ”premature optimization is the root of all evil”. In this case, it wasn’t optimization that caused the “evil”, it was trying to write DRY code when it would be perfectly okay having code duplication. Sometimes, it is encouraged to write the same code twice. Or maybe, the problem was using a Java pattern in a Rails codebase.

That was one of the pains we felt when we started working in this codebase. Another was having to do with accessing our users’s email inboxes. With their permission, obviously.

Accessing our user’s emails

One of the features of this product has to do with reading the user’s email inbox and parsing the email attachments, looking for PDF attachments, in particular. This feature was implemented back in the days where neither Google nor Microsoft had yet to release their API’s to allow access to the Gmail and Outlook inboxes, respectively. So, this was implemented using IMAP. It was what was available at the time so it was the only option. It was still perfectly working when we decided to refactor it. Why did we decide to refactor something that works? Well, for one, the implementation, while it worked, was not ideal. The method responsible for crawling the inboxes was generic in the sense that it would crawl either the Gmail inbox or the Outlook inbox, depending on the user’s preferred email service. That caused the method to be quite long in order to handle the differences between the two services, since it needed to differentiate between the two. And while long methods don’t bother us enough to refactor an entire feature, there was some logic scattered between multiple methods that could perfectly live together in the same place. For instance, we had multiple occurences of this code snippet scattered throughout the codebase.

if provider == "google"

# do something related to Google

elsif provider == "microsoft"

# do something related to Microsoft

endThis is the perfect example to counterpoint the first problem I’ve talked about. This is where abstraction is welcome. Instead of checking in each method that composes the crawler for the provider, we can abstract this into a higher level. We start by implementing a Gmail crawler and an Outlook crawler. Then we go to the highest point of the crawler method we can and do that same check, only now we are only doing it once and calling the appropriate crawler. Each crawler now only has to worry about their respective implementation of how to get emails from an inbox.

The main motivator behind the refactoring was simply to convert to the new REST API that Google and Microsoft provide. We could get rid of some of that indirection, aggregate the logic in a more meaningful sense while we converted to a REST API and got rid of the IMAP implementation. And that’s what we did. Now, the method responsible for crawling the user’s inbox either calls the Gmail or the Outlook crawler, depending on the user’s email service. Everything related to crawling Gmail is in one place, everything related to crawling Outlook is in another. With this we have a more structured and cleaner code, that’s easier to reason about.

When to refactor

There were other major refactors that we did during this last year but there is still more to be done. Refactoring code is not something that you do once and call it a day. Some of the current best practices may change in the future. There might be some new language features or external services that your product could use to simplify something. I’m not trying to say that you should always be refactoring code to be using the new, shiny things. If it works, and the hassle of refactoring would only cause minimal benefits, it should probably stay that way. If you find code that you want to refactor, but there is no real need for that, make a note of that somewhere. The next time you would need to touch some of that code, then consider refactoring. We always try to leave the codebase in a better state than when we first found it. That’s the rule of thumb we tend to follow.

Wrapping up

One thing to have in mind, always, but especially when refactoring code, is that you shouldn’t judge the person by the quality of their code. It doesn’t matter who wrote it. It doesn’t matter why they wrote it that way. It is very easy to judge past code and think less of the person who wrote it but that does not help you with the task of refactoring it.

What matters is how we can make this code better, so that in the future, someone who happens to come across the same code doesn’t have the same frustrations as you did. And chances are it might be your future self that has to refactor the code you are now refactoring, so be kind.